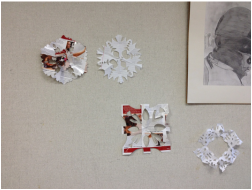

So, today in class, for the first 30 or so minutes, we watched a video on how to make super elaborate paper snowflakes, then I gave students space and time and scissors and paper and let them make their own. (See photo.)

Yes, this is an English class.

And yes, it's still important to do active, silly things like this, even if most observers would question the educational validity of cutting paper and making art projects in a Junior English class, particularly art projects that don't seem to have any connection to the text(s) we're reading or the analytical processes we're learning.

Here's the thing: I got to see a class of 34 sixteen and seventeen year olds regress to about third grade playfulness and be creative. (No, not all of them engaged, but a majority did.) And there are actually lots of English-related and #flipclass-related standards embedded.

For example:

- Students often screwed up a couple of snowflake attempts before they got one they liked. This helped them practice the revision process, and gave them a safe, non-graded place to "screw up." It helped them fail; more critically, it helped them see failure as just part of the learning cycle.

- They watched a how-to video and they followed the steps. This wasn't just "learning to follow directions." This was also parsing an informational text and recreating a process. And the coolest part--since Vi Hart talks crazy fast-- is that many of them didn't get the process on the first go-round. So what happened? They tried once, didn't get it, and then a group of 6 students crowded around my laptop to rewatch the video, and when they struggled understanding that, they looked for other examples. Looks very much like the research cycle to me. And those students who researched more videos and learned how to do snowflakes effectively? They then turned around and taught other students how to do the same.

- It's a great example of metacognitive learning-- it helps them examine and refine their thought processes around learning. Even if they didn't know that's what they were doing.

But my favorite part? There's lots of research that indicates creative work, even silly things like making snowflakes, activates neural pathways and helps humans make connections in other parts of their lives and days. That's all well and good, but I have some important anecdotal evidence to add:

Without exception, the days in which we do silly creative projects at the beginnings of class-- those are the days my students do their best, most focused, most creative work in ALL aspects of class.

Today, for example, I had students re-do analysis videos on a chapter of Looking For Alaska. They had tried last week, and many were low-quality. We did a little scaffolding in class today after the snowflake project, and then they re-made their videos. I watched several before they left, and these videos were better, more thorough, more insightful, and more useful to a wider audience than their originals.

Really, it's the same failure cycle as with the snowflakes. They did one attempt, without a lot of instruction. They did a mediocre job--you could say they "failed." They learned (from me, from a great video Cheryl made) how to find patterns and how to make their analysis much better. They tried again, with vastly better results.

And those are results that are worth every minute spent.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed